Subscribe to the Australian Circular Economy Hub newsletter for the latest circular economy stories and updates on the ACE Hub.

If you had to make a list of your basic needs, what would you write down? Food, water and shelter seem like good places to start. What about healthcare, a political voice, a comfortable home or the all-important WIFI connection? And how does clean air, swimmable oceans and access to thriving green spaces that are rich in biodiversity fit in?

To meet the first set of needs, we need access to resources. But to meet the second set, we need to ensure that our use of those resources doesn’t exceed the limits of our planet. Finding a balance between human needs and planetary boundaries is the basic premise of ‘doughnut economics’.

“Humanity’s 21st century challenge is clear: to meet the needs of all people within the means of this extraordinary, unique, living planet. So that we, and the rest of nature, can thrive,” Kate Raworth, the economist behind the theory, explains during a 2018 TED Talk.

(Watch the fascinating talk in its entirety below or skip to 6.40 for a breakdown of doughnut economics.)

Understanding the doughnut

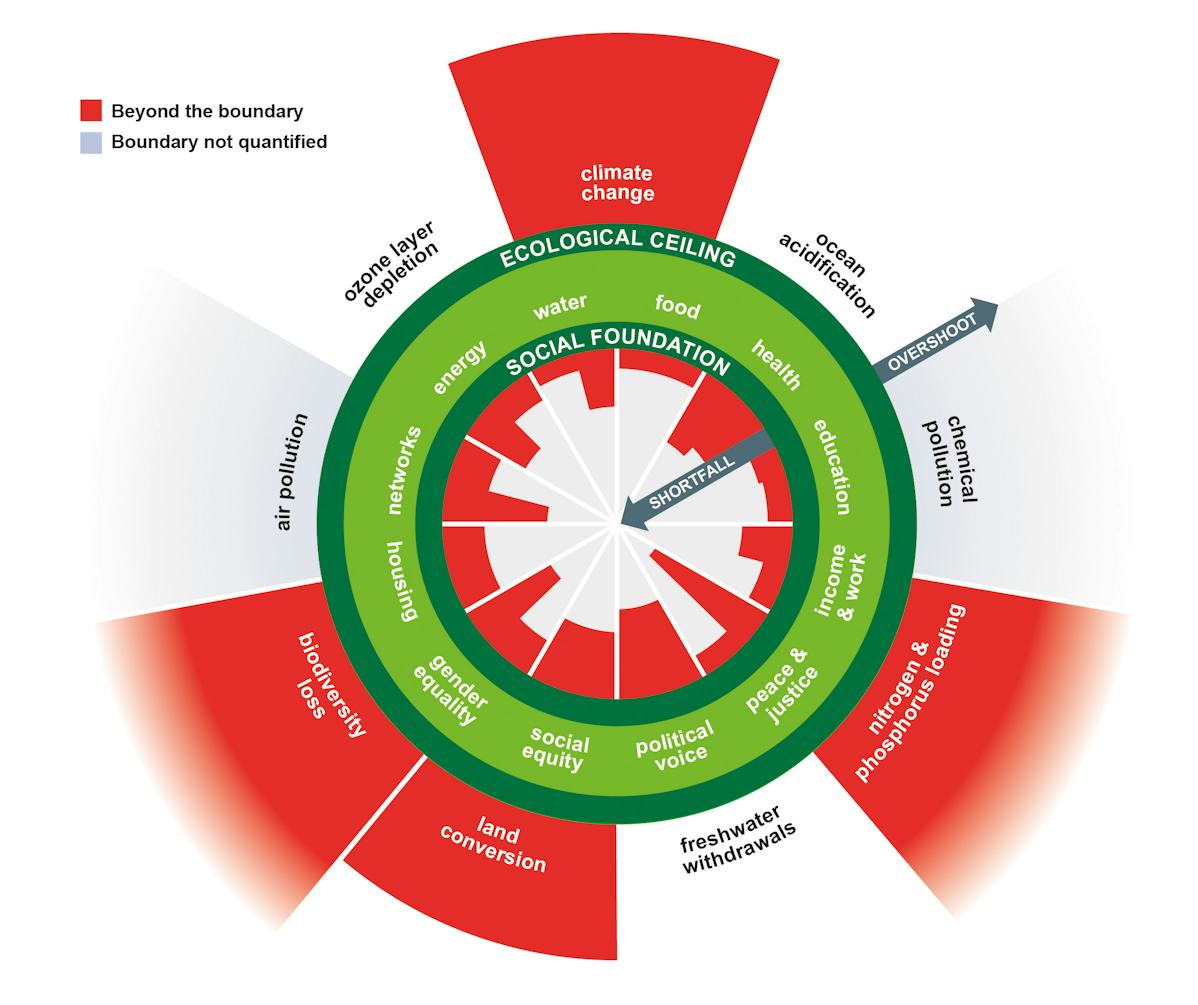

So how do we meet this enormous challenge? The answer, for Raworth, comes in the delicious form of a doughnut. Our basic human needs — food, housing, healthcare, education, gender equality, political voice — form the inner ring of the doughnut. When those needs are not met, we fall into the doughnut hole.

The outer ring of the doughnut represents our ecological ceiling— the planetary boundaries that sustain human life such as a stable climate, clean air, fertile soil and a protective ozone layer. Developed by a group of earth system scientists lead by Johan Rockström, planetary boundaries are the nine natural processes that determine the stability and resilience of Earth.

The sweet spot, and where socioeconomic policy should position us, is in-between these two extremes. In the light and fluffy doughnut dough, where human needs are met without breaching planetary boundaries. Unfortunately, according to the experts, we’re currently failing on both counts.

A diagram of the doughnut of social and planetary boundaries developed by Raworth shows that, collectively, our systems are falling short when it comes to meeting basic human needs and overshooting the earth’s planetary boundaries.

If this is all feeling a little abstract, the ‘2020 Circularity Gap Report’ provides figures on exactly how Australia is performing when it comes to both of these metrics. The report maps countries' progress towards achieving an “ecologically safe and socially just operating space for mankind” by awarding them with a score for meeting human needs (the higher the score, the better) and staying below the planet’s boundaries (the lower the score, the better).

Developed by Circle Economy, the Circularity Gap Report uses the UN’s Human Development Index to measure human needs and an Ecological Footprint indicator to measure resource use in Global Hectares. Australia scored 0.938 on meeting human needs, where the highest possible score was 1. On the other hand, our Ecological Footprint was a whopping 6.64 Global Hectares. These ratings mean that, while Australia is doing well when it comes to meeting basic human needs, we are still ranked as one of the countries furthest away from creating a ‘ecologically safe and socially just’ space.

How does the doughnut help?

So how can doughnut economics help us get back inside this safe space? Into the dough of the doughnut, as it were. In her award-winning 2017 book Doughnut Economics: Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist, Raworth outlines the key principles of doughnut economics. For those of you who are getting tired of reading, these ideas have been translated into some fantastic (and very informative) animations.

1. “Change the goal” — replace the goal of perpetual economic growth, a concept that only delivers benefits for a select few, with that of economic balance.

2. “Tell a new story” — replace the story of neoliberalism with a new story that meets the needs of all life on our planet.

3. “Nurture human nature” — replace the figure of the ‘rational economic man’ (that is central to economic theory) with that of the social and adaptable human.

4. “Get savvy with systems” — embrace economic complexity through systems thinking that is able to identify links between rising wealth gaps and ecological collapse.

5. “Design to distribute” — create economic policy that is distributive by design.

6. “Create to regenerate” — replace the take-make-dispose model with a circular model that keeps resources in circulation.

7. “Be agnostic about growth” — think critically about the promised benefits of economic growth.

The doughnut in action

These concepts are already being implemented in Amsterdam, which is the first city to formally introduce the doughnut model as the starting point for all its public policy decisions.

Organisations like B Corporation are also applying the principles of doughnut economics in the business community. B Corporation is a certification awarded to companies with excellent social and environmental credentials. Businesses with the B Corp stamp of approval are working together to reduce inequality and poverty, build stronger communities, create high quality jobs and improve the environment’s health.

"We envision a global economy that uses business as a force for good," the B Corp 'Declaration of Independence' reads. "Through their products, practices, and profits, businesses should aspire to do no harm and benefit all."

In a 2014 TED Talk, Raworth envisions individuals, businesses and governments sitting around a ‘doughnut table’ and asking how their consumption habits, products or policies could fit within human and planetary boundaries:

“Imagine if each of us put our own lives on this doughnut table and asked ourselves how does the way that I eat, shop, travel, earn a living, vote, volunteer, bank affect humanity’s ability to come into the doughnut?

What if every company, when it sat down to do its business strategy, sat down at this doughnut table and said to itself: is our brand a doughnut brand? Is our core business model helping to bring humanity into that safe and just space between planetary and social boundaries? Or, at the very least, not profiting by pushing people out of it?

And what if the world’s finance ministers of the most powerful countries met and negotiated around a doughnut negotiating table?”

The Australian Circular Economy Hub will provide people with a space to come together and share their ideas about how we can strike the right social and ecological balance in our homes, workplaces and communities.